StAR Project: Reintroducing Zebra Sharks to the BHS by Maurine Shimlock with project updates by Dr. Mark Erdmann

I’m among the fortunate few divers who have seen a zebra shark (Stegostoma tigrinum) in the Bird’s Head. We were exploring for new dives sites, diving just before dusk not far from shore in Triton Bay’s murky flats. Truth be told, I just had a fleeting look at the shark’s long, flexible tail as it rapidly zigzagged away. But that first glimpse of a zebra shark, seen more than fifteen years ago, however, was enough to pique my interest in the species.

As part of our ongoing work in the BHS, last October I wrote about the StAR Project, which seeks to re-establish a healthy population of zebra sharks by bringing aquarium-bred egg cases to hatcheries in Raja Ampat (see StAR updates by Dr. Mark Erdmann below). While Raja Ampat’s reef shark populations are generally recovering nicely under MPA management, zebra sharks are still very rare in the region. Even after Raja Ampat’s MPA network was established in 2007, there just weren’t enough adult zebra sharks left in Raja Ampat to maintain a viable breeding population. Today, the entirety of Raja Ampat’s waters are enforced as a shark and ray sanctuary, and the regency has two of Southeast Asia’s largest and best enforced “no take” zones within its network of nine MPAs. The archipelago also has one of the most diverse tropical marine habitats on the planet, with plenty of underwater terrain to support a robust zebra shark population.

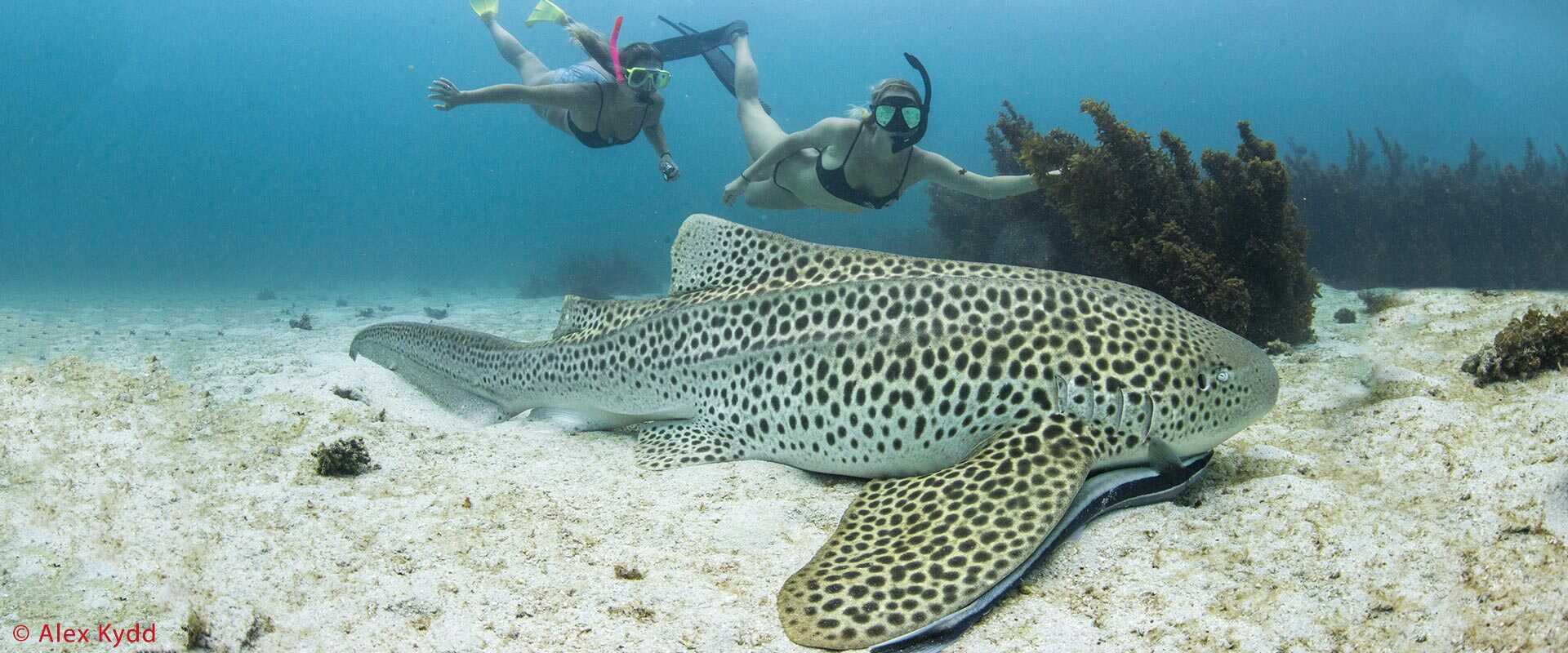

As the only species in their own unique family, zebra sharks are oviparous (egg-laying) bottom-dwelling sharks that range throughout the tropical Indo-West Pacific, from Fiji and the Marshall Islands west to east Africa and the Red Sea. Striped hatchlings are thought to mimic poisonous banded sea snakes (the stripes are also the reason for the common name zebra shark), but within a few months distinct spots appear, and the stripes begin to fade. At one to two years, the spot patterns stabilize, with mature zebra sharks having a distinct leopard-like spot pattern – hence their other common name of leopard shark! These two common names are interchangeable, but it’s important to note that there is another species (Triakis semifasciata) that shares the common name of leopard shark – though this species is found only along the west coast of North America and as far south as Mazatlan, Mexico. Because of these overlapping common names, most American scientists and divers refer to Stegostoma as zebra sharks, but in Australia and the Indian Ocean, they are more typically referred to as the Indo-Pacific Leopard Shark.

Each shark’s spot pattern is distinctive, and can be used to identify individuals, just as in their close relatives, the whale shark. During their 30-40 year life span, zebra sharks feed mainly at night, primarily hunting mollusks and crustaceans and occasionally small fishes. Barbels, or whisker-like organs at the front of their snouts, help them locate prey, while a flexible body allows them to wriggle in tight spaces. During the day, zebra sharks prefer to rest on the ocean floor facing the current so they can efficiently pump water over their gills and breathe while remaining still. If the current is strong enough, this slow-moving shark species has been observed “surfing,” adjusting its fins to remain motionless in open water.

Zebra sharks reach maturity six to eight years after hatching. When mating, male zebra sharks transfer sperm to the female using claspers, or modifications of the pelvic fins. The female can lay up to four eggs at a time and produce 40-80 eggs per year. Covered in fine fibers that keep them anchored to the sea floor, the egg cases usually hatch in about six months. A zebra shark pup may be less than a foot long at birth, but an adult can grow to almost 12 feet and have a tail that reaches half its full body length.

The StAR Project will be supervised by a highly-trained group of Indonesian shark husbandry professionals. The expectation is that enough shark pups will hatch in Raja Ampat to grow into a large, genetically diverse breeding population. Using advanced monitoring techniques including active and passive acoustic telemetry, scientists will follow these zebra sharks as they (re)populate Raja Ampat’s MPAs, no-take zones and the region-wide shark sanctuary. I know I’m not the only diver who wants to see more zebra sharks underwater, and I’m optimistic that within the next decade diving tourists will again commonly see zebra sharks around reefs throughout the BHS.

Maurine Shimlock is a co-administrator of the Bird’s Head Seascape website. For more about Maurine visit her website, Secret Sea Visions.

Updates on StAR project from Dr. Mark Erdmann: Despite the significant logistical challenges caused by COVID, the StAR project steering committee is extremely pleased with the progress made to date and is looking forward to the first shipment of eggs to arrive in Raja Ampat by mid-2022! The West Papua Provincial Research and Development Agency, BALITBANGDA, is now leading the project in Indonesia and is currently finalizing the permits to import the eggs. Our aquarium partners in the US, Australia, and Hong Kong have now identified all of the genetically-appropriate adult brood stock from which we’ll source the eggs, and have initiated the breeding program. With much appreciated support from Fondation Segré, the Rumah Foundation, MAC3 Impact Philanthropies, Save the Blue Foundation, the Henry Foundation and the Ingegerd Mundheim Estate, we’ve now finalized construction of one of the Raja Ampat hatcheries (with the other soon to follow), and we’ve recruited all four of the local hatchery aquarists in Raja Ampat – who will soon go through an intensive month-long training course at the Jakarta Aquarium. Once they’re back in Raja Ampat, they’ll complete the setup and initialization of the hatcheries, in order that we’re prepared to receive the first shipment of eggs – hopefully by late May or early June. Stay tuned for more updates soon!

Administrator’s Note: Since very few divers have ever seen a Leopard Shark in Raja, much less photographed one, all images in this story were taken elsewhere. The images for this article, other than of the hatchling, are kindly provided by Australian-based photographer, Alex Kydd. Alex, an ocean biologist with a degree in Environmental Science, creates images all over the world. His images are beautiful, and you will appreciate them even more knowing that most were taken while snorkeling! The Bird’s Head would like to thank Alex for the use of his images and his support for StAR.